It turns out the positioning, tantrums and hot air of leadership struggles in electoral politics are useful for something – they give us an opportunity to look at frames and story-based strategy.

Back in 2007 I wrote an article for the Change Agency’s enews about framing in the federal election campaign, and specifically the contrast between ‘working families’ and the Howard era frame of ‘battlers’. The recent struggle for the ALP leadership between Julia Gillard and Kevin Rudd provides an another interesting opportunity to look at framing.

George Lakoff, the most well known progressive proponent of framing, defines frames as ‘mental structures that shape the way we see the world’ (Don’t Think of an Elephant, 2004). Frames are about values, and they define ‘common sense’ for us – if information doesn’t fit our view of the world, it tends to bounce off. Language activates our frames, and the language used in political discourse can be key to connecting with people.

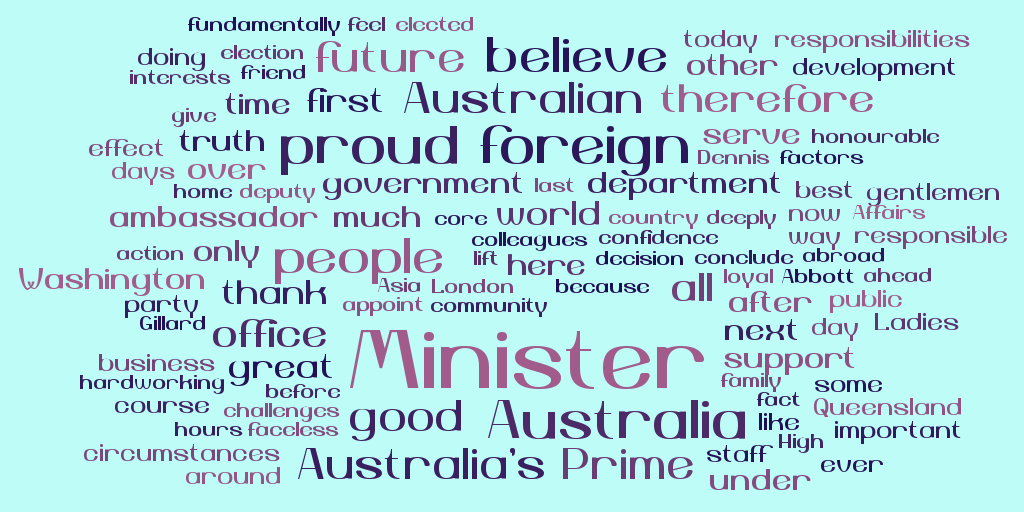

Lakoff makes the point that frames will be most effective when they relate to widely held values. This world cloud of Kevin Rudd’s resignation speech on February 22 is interesting:

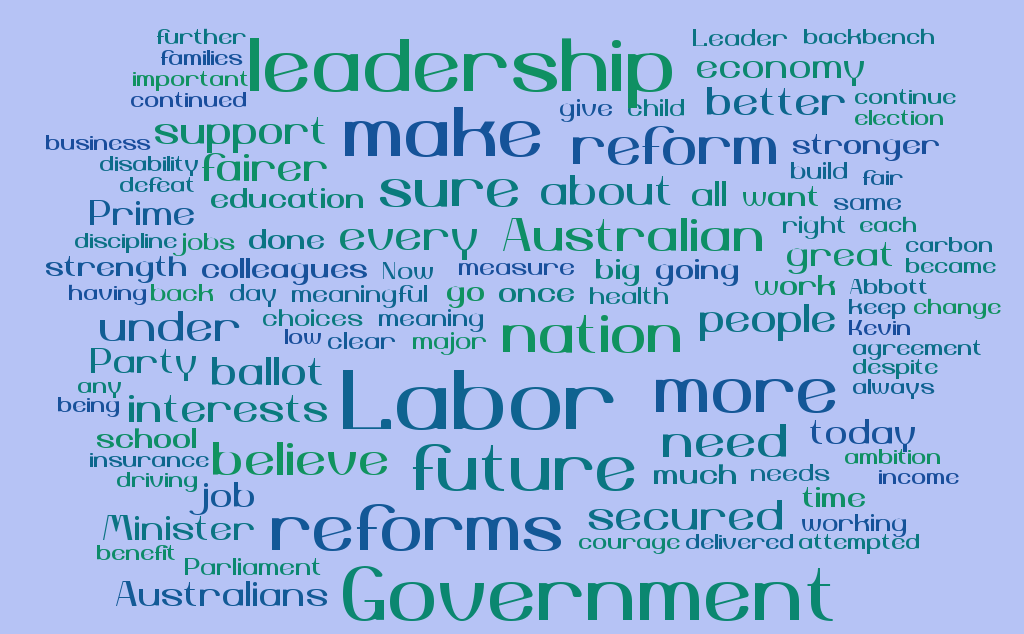

The repeated use of Australia/Australian/Australia’s, and the Australian people is noteworthy. Rudd is tapping into widely held values around Australian democracy. ‘Future’, ‘believe’ and ‘proud’ also occur frequently, showing an emphasis on communicating vision and personal belief (however sincere). By contrast Gillard’s speech announcing the leadership ballot, presented to a press conference on February 23, is represented below:

The cloud shows Gillard talking about Labor, the government and reforms a lot, less about Australian people. Like Rudd, Gillard talks about the future, and interestingly ‘make’ is used a lot. The Prime Minister in this speech and later statements has placed a lot of emphasis on her role in making things happen, delivering on the ALP reform agenda. Gillard uses a frame of ‘hard work’ (as a moral value, as a contrast to her ‘chaotic’ opponent) and ‘discipline’ which have been the main values statements she has made during her leadership – tapping into Labor themes of the ‘dignity of work’, the Protestant work ethic, hard work as virtuous, godly, and deserving reward. While a fairly widely held value this appears to not necessarily resonate in the Australian public. Gillard emphasis on getting the practical work done in contrast to her opponent’s ego and flashiness also references gender differences.

In his resignation speech Rudd speaks directly for the first time publicly about losing the ALP leadership and position as PM – but it’s a familiar story because we’ve been hearing it ever since it happened, predominantly from Tony Abbott. That is, that he was subject to a ‘stealth attack’, a ‘coup’, a ‘political assassination’ (this term not used by Rudd, but widely used in the media), pulled down by factional power-brokers. He fits his resignation as Foreign Minister directly into this story – saying his position has been undermined by ‘faceless men’ and comments which have questioned his integrity. He attempts to make the story about the PM’s lack of confidence in him, rather than his undermining of her.

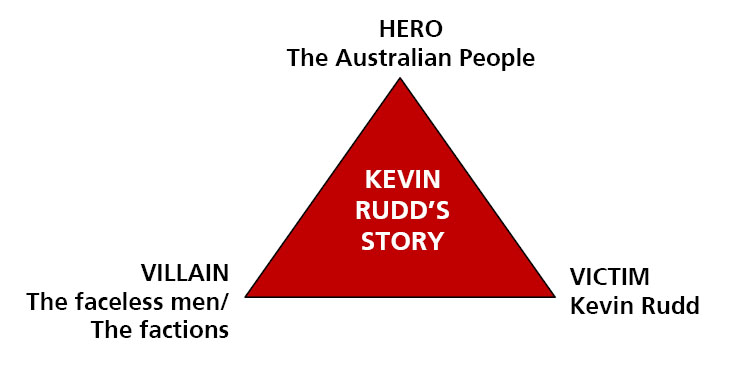

The Drama Triangle is a great tool I picked up from smartMeme, as part of their story-based campaign strategy curriculum. The Drama Triangle is a neat way to summarise the central conflict and characters in a story. Compelling stories tend to have a Hero, Villain and Victim. Here is my interpretation of the story Kevin Rudd has been telling:

That is, Rudd has been victimised by the faceless men, and the Australian people are the heroes who through ‘people power’ can put things right. Rudd positions himself as a well-intentioned monarch deposed by corrupt careerists, waiting to be restored to his rightful position. This is consistent with the ‘coup’ frame – the definition of a coup is ‘a sudden, violent, and illegal seizure of power from a government’.

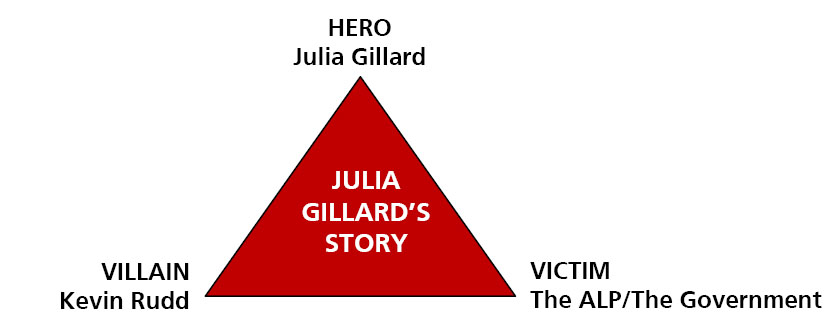

In response to Rudd’s resignation ALP MPs who support Gillard have gone public about their experience of Rudd as PM, and their allegations of him undermining the government. The difficulty is that Rudd got there first with the framing. Talking about treacherous acts that undermine an elected Prime Minister brings to mind Rudd’s unseating by Gillard. It also confirms Rudd in the Victim position. Many have commented on Gillard’s lack of explanation for why she took the leadership, and what has come out recently may look like too little too late for many voters. If there is an assumption that Gillard became PM dishonourably, and her government is not legitimate (as Abbott has repeatedly reinforced) there is no moral high-ground to take about being undermined or sabotaged. Here’s my interpretation of the story told by Julia Gillard and her supporters:

That is, Julia Gillard has heroically cleaned up the mess caused by Rudd and guided a reform agenda. Kevin Rudd has undermined the functioning of the government, sabotaged the ALP’s 2011 election campaign, and got in the way of communicating the government’s achievements.

The contrast between the two triangles is striking. Which is a more sympathetic victim, Rudd with a high approval rating, or the ALP which is on the nose? Which is a more compelling hero, the valiant Australian people, or a PM polling terribly?

Rudd’s story is a well crafted campaign story, while Gillard’s may resonate with people inside the ALP and its rusted-on supporters, but has little broader appeal. Gillard is lucky the ballot has nothing to do with ‘people power’ – but the truth never got in the way of a good story.